1

Åsa Lindström

School of Business and Economics, Linnaeus University

asa.lindstrom@lnu.se

Abstract

Assessment and examination in higher education takes place in a complex context where many perspectives affect; management, academic developers, students and not least teachers. That assessment strongly influences students’ learning is well documented (Gibbs 1999; Marton 2005). The study’s starting point is that a better understanding of how teachers really relate to this very important part of the teaching profession, create better prerequisites for working continuously to enhance the quality of higher education. The purpose of this study is to describe university teachers’ perceptions on assessment and examination as a basis for creating conditions for the development of grading as being a strong influencing factor in student learning. The method is a combination of questionnaires and interviews, thus both qualitative and quantitative methods was used to collect data of both qualitative and quantitative nature, which was analyzed with both qualitative and quantitative methods. Results show the relationship between the conditions, criteria for what is regarded as assessment and examination of good quality, and the development of the same. The empirical results also identify diverse perceptions to a variety of aspects related to assessment and examination, but also educational development in general. The importance of knowledge transfer is repeated where discussions and explanations between colleagues and students, in order to create meaning and development is required.

Key words: academic development, assessment, assessment culture, examination, grading, knowledge transfer

Introduction

The everyday context of teachers, at all levels of education, include assessment, and for students it involves being assessed (Marton 2005). Moreover, he states that assessment, and the grades it result in, is the most important form of influencing the way people learn in general. In other words, young pupils, as well as students of higher education, predominantly learn what they expect to be graded upon. Schools are basically evaluative settings, Lundahl (2006) agrees, and continues stating that it is not only what you do there, but what others think of what you do that is important. Teachers engage in both formative and summative assessment of multiple forms (Taras, 2008). The final result, not rarely, is deciding a grade. In the best of worlds, a grade that in a just way reflects the student’s performance. A key assumption in this paper is to acknowledge the role of the teacher to promote student learning. Hence, the focus is on the teacher’s perspective on grading, with the intention that an understanding of the university teachers’ perceptions can better shape education, including assessment and grading, which supports student learning. This study has posed questions such as; what is their opinion on different forms and scales of grading? And what about different categories of teachers; are more experiences teachers reluctant to change, more so than their younger colleagues? In the context of grading, the criteria used is an operative factor (Sadler 2005). Therefore, one might wonder if teachers agree and in what way they use criteria and set grades. Understanding of teachers’ views of grading is a necessary prerequisite in order to be able to improve the quality if learning as being one of the great challenges for institutions of higher education worldwide (Boud et al. 2010).

The purpose of this study is to describe university teachers’ perceptions on assessment and examination as a basis for creating conditions for the development of grading as being a strong influencing factor in student learning.

Theoretical framework

If you should choose to single out one measure to improve education quality and enhance student learning, you should consider the assessment system, where grading is a significant component. Rowntree (1987) states that if we wish to discover the truth about an educational system, we must look into its assessment procedures. He further explains the dynamics of assessment and the relation to grading, describing grades being based on assessment of different kind; a result. Sadler (2005) defines that assessment refers to the process of forming a judgment about the quality and extent of student achievement or performance, and therefore by inference a judgment about the learning that has taken place. Grading, in turn, refers to the evaluation of student achievement on a larger scale, either for a single major piece of work or for an entire course, subject, unit or module within a degree program. It is not a clear-cut distinction between assessment and grading as terms, hence making in challenging to elucidate. There is no doubt that assessment is of the outmost importance when it comes to influencing student learning, their behaviour and results (Gibbs 1999, Biggs 2003, Boud & Falchikov 2007, Harland 2015). The ability to manage the process of assessment and the act of grading, hence aiding students to develop strategies for handling different kinds of academic assignments, is the most significant task being a teacher of higher education (Gillett & Hammond 2009). However, assessment in general and grading in particular, is not undertaken is isolation, but as part of a wider context. Biggs (2010) refers to the correspondence between learning objectives, course content, structure, teaching and assessment, as ‘aligned teaching’. This principle is established as part of a European approach to quality, which includes concepts such as learning outcomes and clear student-centred perspective (Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area, 2015). The standard on student-centred learning, teaching and assessment explicitly underline the importance of assessment for the students’ progression and their future careers.

Taras (2008) believes that it is central to everyone in higher education, not just specialists, to understand assessment on a deeper level; its terminology, processes and relationships between them. Her results, however, show the opposite that knowledge about assessment is often fragmented both theoretically and practically. The conclusion is to chart through which processes assessment is done, to be clear about what we do and how. It also enables evaluation of both how the students’ learning is influenced and the teachers’ assessment (Taras 2008). To covet a deeper understanding and consider assessment and grading in a broader context seems to improve quality (Dahlgren et al. 2009). The overall view of a system of components that strongly dependent on each other, rather than considering assessment and examination as individual phenomena, is illustrated:

“Examination in higher education as well as in all part of the education system is a highly interdependent system of grading, assessment tasks, judgement criteria, students’ approaches to learning and features of the learning outcomes.” Dahlgren et al. (2009:193)

Aligning learning outcomes with assessment and specifying assessment criteria are frequent objectives where institutional learning and teaching strategies focus on assessment (Gibbs & Simpson 2002). However, they race an alert, underlining that it is not only about the measuring of student performance – it is about learning. With an international perspective, universities face major changes in the near future (Boud et al. 2010). In the article ‘Assessment 2020: Seven propositions for assessment reform in higher education’, some 50 researchers and academic developers from e.g. Australia and the United Kingdom have made concrete proposals on how assessment in higher education can be reformed (Boud et al. 2010). Rust, Price and O’Donovan (2003) assume that there is increased demand for higher education assessment in a more transparent manner for all parties involved. This demonstrates better reliability in grading and satisfying increasing demands from reviewing agencies to prove what results are being created. Rust et al. (2003) focuses on how to increase understanding of the assessment process and its criteria among students. An important conclusion was the importance of both students and teachers expressing the need to discuss criteria to make its application comprehensible. If not, there is a risk of a ‘Hidden Curriculum’ (Snyder 1971) where hidden knowledge, ‘tacit knowledge’, fill the gaps. Rust et al. (2003) warn of an exaggerated belief in ‘explicit knowledge’, the more explicitly expressed form, for example, in an assessment matrix. An understanding of both forms of knowledge of assessment must be developed by both teachers and students. Thus, it is not enough only the explicit formulation of assessment templates or criteria, but a socializing process is required where understanding is created and the explicit knowledge is transmitted (Rust et al. 2003, Sambell, McDowell & Montgomery 2013).

Dahlgren et al. (2009) emphasizes that assessment criteria in higher education are often problematic in formulating and not in itself leading to high quality or promoting student learning. Instead, it is in the discussion between teachers, and between teachers and students, that the criteria become meaningful and can be applied in a manner that gives the positive effects sought. Discussion in this context involves formulation, negotiation, application, rewording and critical reflection (Dahlgren et al. 2009). Even small changes in methods and tasks can give immense impact on student behavior and study results (Gibbs 1999).

”Students are tuned in to an extraordinary extent to the demands of the assessment system and even subtle changes to methods and tasks can produce changes in the quality and nature of the student effort and in the nature of the learning outcomes out of all proportion to the scale of the change in assessment.” Gibbs (1999:52)

Gibbs, Hakim and Jessop (2014) have found tremendous dissemination regarding assessment and application of assessment criteria. They emphasize the value of developing a common collegial assessment culture to promote student learning. When the students are constantly assessed based on very different premises, the feedback value becomes marginal and the progression through an education becomes unclear. There is evidence that subjects and corresponding academic groups create distinct assessment environments linked to traditions, rules, perceived demands or myths about how assessment is done (Gibbs, et al. 2014). They address the question of whether this affects students’ learning, especially students who meet representatives of different disciplines in their education. They say, among other things, that there are significant variations in quality, quantity and timing of feedback in connection with assessment of examinations. This in turn, resulted in students perceiving feedback as unreliable and not useful for developing their abilities in future tasks or courses. An existing culture, or approach, is that assessment is an intuitive process that cannot be formulated explicitly, as illustrated by the following quote.

“These words uncannily echo the normative, ‘connoisseur’ model of assessment typified by the phrase ‘I cannot describe it, but I know a good piece of work when I see it’. A model of assessment judgement most often likened to the skills of wine tasting or tea-blending, and ‘pretty much impenetrable to the non-cognoscenti’.” Webster et al. se O’Donovan et al. (2004:328)

Criteria-based strategies for assessment and grading in higher education have increased in use as a consequence of good theoretical motivation and its educational effectiveness (Sadler 2005, O’Donovan et al. 2004). However, there is no consensus on what criteria-based really means. Sadler (2005) has compared 65 universities in Sweden, UK and Australia, all of which have grading policies that claim to be criteria-based. Although those type of policies has a broad desirability, there are different conceptions amongst higher education institutions of what it means in theory and in practice, according to Sadler. To pin-point a common denominator, criteria as a term is explained as attributes or rules that are useful as levers for making judgments. Sadler (2005) also adds that judgments can be made either analytically, built up progressively using criteria, or holistically without using explicit criteria. Furthermore, four different grading models and their connection with criteria are identified; 1) Achievement of course objectives; 2) Overall achievement as measured by score totals; 3) Grades reflecting patterns of achievement; 4) Specified qualitative criteria or attributes. These different models of grading can come on a collision course with each other. For instance, the third model ranks poorly if grading criteria prescribe the second model. There are many situations in which a rule for adding sub-points gives obvious discrepancies in terms of qualities that appear to be contrary to the university’s best assessment of a student’s achievement. A weak development of a student in certain areas can be compensated by superior performance elsewhere. When a total sum is calculated, patterns of strengths and weaknesses may be lost (Sadler 2005). The fourth type of grading model has grown in use in recent decades. The conclusion that specified qualitative criteria or attributes increased in use summarize challenges; to examine how criteria and standards can be contextualized, to negotiate and reach a consensus on appropriate levels of standards, to allow students to make assessments using standards, and finally to apply the criteria consistently when grading (Sadler 2005).

Harland et al. (2015) has studied university teachers’ experiences and the results showed that, among other things, teachers had no idea how many examinations the students were exposed to, and there was weak communication between teachers, departments and programs. Assessment can be regarded as a very difficult task. Barnett (2007) problematizes assessment in higher education and asks whether it is even an impossible task. He believes that in our complex and constantly changing contemporary setting, it is almost a mission impossible to assess knowledge, understanding and skills at the level of higher education. Reimann and Wilson (2012) argue that in order to improve student learning, teachers’ perceptions of teaching and assessment must change. Certainly, perceptions may differ from actual behavior, but Reimann and Wilson (2012) still point to perceptions as a prerequisite for achieving change. This, in turn, motivates the focus of this study teachers’ perceptions. The research question was formulated as follows; how do university teachers perceive assessment and examination in higher education?

Methods

Prior to this study, many perceptions were observed among colleagues who were quantitative in nature, for example; ‘Most teachers think grading criteria are meaningless and impossible to formulate.’ Was that really the case? These observations led to the selection of a quantitative first part of the study; a survey. The population consisted of all teachers at Linnaeus University, located in southern Sweden. The education and research at Linnaeus University’s is conducted within a wide range of subjects within the Faculty of Engineering, Business and Economics, Humanities and Art, Health and Life Sciences and Teacher Education (Linnaeus University 2015). The data collection generated 202 responses with good dissemination between the five faculties. The results were distributed with a spread of 13% response from the Technical Faculty, to 23% at the School of Business and Economics. The data types that were collected were of quantifiable type, e.g. number of active service years in higher education, as well as qualitative type, e.g. questions about perceptions. Regarding how long respondents have been working as teachers in higher education; the results were categorized into four segments; 0-5 years, 24%; 5-10 years, 21%; 10-15 years, 23%; > 15 years, 33%. The distribution shows a good spread between different scientific disciplines, as well as between more experienced teachers and those who are newer in their role as university teachers.

The results of the survey identified interesting observations, which were sought explanation and understanding of through a second part of the study; qualitative interviews with a targeted selection (Bryman 2011). The ambition was that the chosen respondents could contribute interesting explanations and interpretations of the survey results. The distinction between qualitative and quantitative methods does not need to discriminate in perspective or approach. Qualitative perspectives are not synonymous with qualitative methods. It is thus fully possible to apply quantitative methodology in the context of qualitative perspectives. Data compilation and analysis was carried out using descriptive statistics, significant tests through X2 analysis, and thematization depicted by a constructed framework matrix (Richie et al. 2003, in Bryman 2011). To categorize the results on how grades usually are decided on a specific examination, the grading models of Sadler (2005) was used.

The content of this paper was presented at the pedagogical conference Lärarlärdom in August 2017 at Blekinge Institute of Technology, Sweden, and constitutes a selection of results from a larger study where a more thorough description of methods can be found (Lindström 2016).

Results

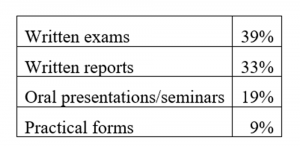

University teachers’ perceptions on assessment and examination, resulting in setting grades, was examined through questions concerning; 1) forms of assessment, 2) methods of grading, and 3) scales of grading. Firstly, the study shows the most frequently used forms of assessment on the courses they normally teach. The intention of the question was to give a picture of how the teachers work with different forms of assessment, without locking them into predefined alternatives or entering a certain number of possible forms of assessment, which justifies the open character. In data processing, the answers have been categorized into four types: written exam, various forms of written reports, oral presentations/seminars, and practical forms such as laboratory work, clinical examination and design. How common these different types are is illustrated in the table below.

Table 1. Most commonly used forms of assessment

Combination response that indicated more than one form was frequent on this question. The most common form of use as the sole form of assessment was the written exam, as indicated by 46% of respondents. Thus, there are just over half that use written exams in combination with any other form of assessment. The second most common form is written reports, which includes written work that may be termed PM, paper, essay or the like, is used in combination with other forms in 73% of the answers given. The form that is combined to the highest extent was oral examinations; 94%. While practical examinations are combined in 85% of cases.

The results reflect the teachers’ perception of the most common forms of examination, which is not equivalent to the actual forms. However, the purpose of the question was, in addition to giving this image, to serve as an input to the following question of any desire to change them. The tendency to change methods of grading was depicted by inquiring ‘Would you like to change the forms of examination you mostly use today if it was practically and in terms of resources possible?’ This hypothetical question showed that 69% would not like to change their examinations. The remaining 31% answered the supplementary question as to what they would like to change. This resulted in a highly diversified response, as shown by the following diagram.

Diagram 1. Desired changes of forms assessment

The highest frequency was given to requests for more oral examinations; 15%. It is supported by respondent views on how to make the most effective examination. The next size largest group consists of requests for more variety in the different forms of examination used, and the desire to work more with continuous improvement; 12% on each proposal. One respondent argues: “Most of all, that change is good, both to elevate different skills of the students, but also that I, as a teacher, will be developed and inspired.” Variation was also highlighted in several comments, for example: “A variation in forms of assessment is preferable for both students and teachers. A variation favors the ability to reflect and learn in different ways.” In addition, there were comments that included more oral elements, individual examinations to a greater extent, and more practical elements. It can also be noted that about as many, 7% and 8%, respectively, want fewer written exams versus more written exams. It can be noted that all examinations does not serve the same purpose and balance the often massive criticism of written exams. It’s not as simple as saying that written exams are always bad. The category “Other” contains, for example, comments such as the forms of examination can easily be changed with unchanged resource allocation, and suggestions like: “More ’open’ exams where I grade students ability to argue for their ideas, in an on-going conversation.”

The number of active years as a teacher in higher education had no significance for change propensity. The result showed very little dispersion; between 67-71% for No and 29-33% for Yes, and no significance for the differences with an X2 of only 0.11. Among the scarce thirds who indicated that they would like to change the types of assessment that are mostly used today if it was practical and resource-friendly, there was the opportunity to comment. The categorization above of these answers shows a diversified image. However, it is not only what answers are given that are interesting, but also what is not commented at all, or to a very low degree. For example, there was a very low degree of comment regarding student engagement; 2%, formulated in an answer: “Have a higher degree of student assessment; both of their own achievements and of other students.” Compilation of interviews also support the presence of different models of grading, as illustrated by the following quotation from one respondent:

“Here we put numbers on things. If you have 60%, you have actually passed. Other departments have their culture. Comparing the student’s overall performance throughout the course, including seminars, discussions, reflections and submitted exam papers and possibly practical examinations, which makes it extremely difficult to put numbers. These are quite different cultures!”

The argument posed suggests that different forms of assessment involve different degrees of subjectivity, but that numbers are subjective too. There are definitely different cultures at different departments and it is about adapting, is a frequent view. One respondent describes a similar type of differences within departments and subjects. They distinguish between more technically oriented and business-oriented courses within the same subject, which have completely different assessment practices.

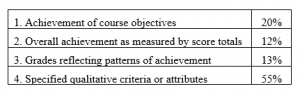

Secondly, to learn the methods of grading used, how the respondents usually decide which grade a student gets on a specific examination (regardless of scale), was investigated. When the university teachers in the sample of this study commonly set grades the complied results show that specified qualitative criteria or attributes dominate; 55% of respondents were placed in the fourth category using Sadler (2005). Even though the question was designed with open-ended response, the answers were easily categorized based on answers like: “Using given criteria compiled with colleagues according to the requirements”. The table below shows the overall division.

Table 2. Grading Models (Sadler 2005)

One fifth indicates that the course objectives, category 1, determines the grade a student receives, while just over ten percent gives answers categorized within 2. Overall achievement measured by total score, as illustrated by answers as “According to a percentage of marks on the written exam.” Category 3. The grade reflects patterns of achievement, is approximately the same extent and can be exemplified with explanations like “I set grades based on knowledge learning; i.e. what has the student understood and how can the student use the knowledge.”

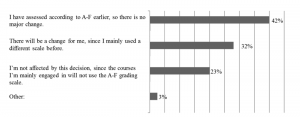

Thirdly, perceptions on scales of grading was investigated; for two reasons. Due to the fact that Linnaeus University, where data was collected, recently changed scales of grading, but even so still uses four different scales across the university. This implies that different teachers must adapt to several scales, as must many students. The second motive was present critique against moving from a scale with few grading levels to a more finely divided one, such as is the case of Linnaeus University. The argument being that more grade levels risk controlling students towards more shallow learning. A current question regarding grading concerns the grading scale used; a scale with few levels, such as Pass/Fail only, or a multi-level scale such as A-F. Finding out what experience is available from different scales enables analysis of different perceptions based on experience. Thus, a survey question was posed: “The Rector has decided that a seven-point grading scale, A-F, is introduced at Linnaeus University from the autumn term 2015. The A-F scale will be used in all courses where international students can attend. What best describes you?”

Diagram 2. Experience of assessment according to A-F grading scale

The majority of the respondents, 42%, have experience of assessing according to A-F. A relatively large proportion, 32%, has mainly used a different scale and therefore will have to change the way they assess and grade. Among the few who stated ‘Other’, and used the free text option, there were some comments that all courses should have A-F, but also those that articulate risks. One comment describes the risk of the level of approval being lowered: “I have done both, evaluated, and saw that there is a need for discussions concerning the risk of A-F lowering what is regarded to be a pass grade.” Another comment highlights the time perspective: “It will require more time by both teachers and students before the scale will provide measurable difference, is my spontaneous insight.” Perceptions differ and some argue that a multi-level scale does not have any positive effects, while others describe: “A-F, a scale that gives both the student and the teacher a good educational tool in their learning and understanding of their own and the others learning processes.”

In order to investigate the perception of switching to A-F is predominantly positive or negative, the question was asked; “Whether switching to the A-F scale affects you or not – what is your opinion?” The result showed that a majority, 44%, found it positive, and 31% indicated that it was predominantly negative. 25% had no opinion. A comparison of the answers to the outcome of this question and the number of active years as a teacher in higher education, showed that the number of years of service did not significantly affect positive or negative perception, or no opinion. A weak correlation could be identified between the 0-5 year of service with 29% responding to “no opinion”, while 21% in the group >15 years had no opinion. In other respects, the result showed great coherence in this regard. When clustering the two groups with the shortest time as active teachers in higher education and the two with the longest experience, it also showed a weak connection. In the 0-10 year group, 38% were positive and in the group >10 years, 48% were predominantly positive.

The result showed stronger correlation with a comparison of predominant positive versus negative perception, compared with previous experience of assessing A-F. The most positive group were those who stated that they assessed according to A-F earlier and therefore did not experience any major change. In this group, 68% were predominantly positive, 13% predominantly negative, while 19% responded no opinion. This difference is significant at the 0.1% level (X2 = 20.7) compared with those who used a different scale earlier and therefore experience a change. The analysis thus showed that the experience of seven-grade assessment creates a more positive perception. The qualitative results also provide confirmation of the relevance of experience, for instance, one respondent testifies on how to develop their assessment ability in line with the number of active years.

To summarize; a profound consensus was identified regarding the significance of assessment and grading, as illustrated by comments such as: “Important, as it controls students’ learning!”; “We need to get better at it.” And; “There’s a need for many discussions about this, to ensure just assessment of good quality”.

Discussion

The result shows a diverse picture of perceptions; which types of assessment that are preferred, what grading scale or what actions that should be prioritized. Even current assessment cultures showed rich variations. Patterns that can be identified are that assessment questions are perceived as important and there is a demand from teachers for recognition of educational work in general. The perception is that teachers who engage in student learning and take time to develop, for example, assessment forms and grading are a bit strange; “It’s not illegal to be interested in development of teaching and assessment, but it’s a bit odd”, is a comment that has been left. Clear signals from management are required; not only in words but in action. Empirical results and theory show a large dispersion regarding assessment and application of grading criteria, which gives reasons for forming common collegial assessment cultures. A department or academic discipline is part of an organization, that is also characterized by a culture; an organizational culture, which the assessment culture is a part of.

Confidence and commitment are words that are repeated both empirically and theoretically. Management is one variable, but the teachers’ attitudes and actions are also culture-creating. Confidence enables sharing of knowledge and experience, as well as creating the discussion described in the theoretical framework regarding assessment. For instance, explicit grading criteria in courses are not a quality-creating universal solution as such, but the process between teachers and students to create, implement and revise, is promoting student learning and quality-driven education. Higher education consists of a great number of academic disciplines and degrees. Respect for diversity is required; that different subjects have different assessment practices. Nonetheless, common denominators, such as assessment, clearly guide students’ learning, and that its design needs to be noted. One question that engages is the seven-grade scale A-F and whether its application is predominantly positive or negative. In theory there is criticism; so even among the respondents. However, the results showed that the majority thought it to be predominantly positive, a proportion that increased significantly with experience. The manner in which grades are usually set, has been categorized and shows a clear overweight for specified qualitative criteria, which is consistent with trends described in the theoretical framework. Assessment criteria together with the requirement to achieve course goals represented ¾ of respondents’ responses and thus dominate. That finding also reinforces arguments for working consciously and systematically throughout the assessment process.

Transparency, in the sense of clarifying to all parties involved, how assessment and grading is conducted, is imperative. Theory strengthens both this result and demonstrates a tendency where demands for increased transparency can be observed both nationally and internationally. There are perceptions present, that one would rather want to proceed by themselves and do as they please, without interference and definitely not be subjected to scrutinizing eyes of any kind. The dominant perception though, is that transparency is desirable and something we will have to get accustomed to, if we have not already done so. Conversely, seeking transparency is not unproblematic, since the use of concepts and international comparability can create confusion. Transparency is not just a requirement for clear processes, but also clear conceptual use. For instance, it may counteract complications with international comparability, as well as misperception concerning application of terms and concepts, if we can demonstrate clearly both the assessment process and its criteria. A conclusion is to emphasize the benefit of sharing and valuing colleagues’ experiences.

Propensity to change was identified as a category of quality in the empirical thematization. The result recognized which forms of examination that are most common in occurrence. On the basis of that, it was found that most, more than two thirds, would not like to change their forms of examination, even if it was practically and in terms of resources possible. For this cluster, it can therefore be ruled out, that lack of time and resources is considered a barrier to changing forms of examination. Among the scarce third that would like to change, the findings show a wide spread of desired changes, such as more oral examinations and greater variety. The question was hypothetically posed, and how many respondents think they actually have sufficient resources and other conditions to fulfill their wishes, does not appear. Even though, the results show that the number of active years as a teacher did not have any significance for propensity to change. This conclusion contradicts some of the respondents’ perceptions. It does not therefore have to be the case, that teachers with more active years become comfortable and not willing to change, instead experience can create a momentum and ability to see opportunities that less experienced colleagues do not acknowledge. The reflection underlines the added benefit of getting acquainted with colleagues’ understanding of the various aspects of assessment.

Knowledge transfer is a recurring quality criterion both empirically and theoretically. Discussions and explanations are required between colleagues, and with students, in order to create meaning and development. It is also intimately associated with the requirement that grades be argued for in agreement with set goals and criteria. To realize this necessary knowledge transfer, also requires that conditions in terms of time and resources exist. Since assessment is not performed in isolation, an integrated approach is required that also involves goals, teaching methods and feedback. Combining explicitly formulated assessment criteria with the socialization process of the more implicit parts, need not be that resource-intensive. The main insight is that this is actually needed at all, as well as conversations with colleagues and students.

“How do university teachers perceive assessment and examination in higher education?” was the research question posed, with the purpose of describing the very same and thus creating conditions for the development of grading as being a strong influencing factor in student learning. With a comprehensive interpretation, one might not say that this was fulfilled. Still, within the limits of the study, a contribution has been given, which may hopefully be inspiring, and perhaps even influential. Given the importance of assessment for student learning, it is a prerequisite for achieving good quality, or even excellence, to work consciously and strategically with educational development in general and assessment in particular.

Concluding remarks

Teachers’ perceptions exist in a context of conditions that cannot be ignored. These are the basis of criteria for what is considered to be good quality and what is possible to implement. Institutions of higher education must balance commitment and prerequisites. In general, what you want to achieve, the driving force, motivation or even passion, to actually work with and against the ambitions of both management and teachers. Those who show dedication want to experience recognition for what they achieve and that their experience and knowledge are given value. This goes for both teaching and research, which in an ironic sense, often are perceived as conflicting activities. One argument that could possibly help to reduce the gap between research and educational activity is the view that it is basically one and the same. These are both processes where knowledge will be problematized, measured and generated. Certainly, epistemological assumptions may differ, but if such a supposition is rooted, it could inspire a new way of considering assessment questions.

The creation of academic development in general and assessment in particular is based on the criteria identified. One reflection is whose interpretation and prioritization of criteria that take precedence; teacher, student, management, administration or maybe any other stakeholders such as external auditors or professional academic developers. Illuminating possible different perceptions makes it possible to ascertain common basic criteria as a starting point in development work. Is it a goal to create an examination that demands students to spend 40 hours a week on studies? Or is it most important to distinguish students by differentiated grades? What will create the desired outcome? Academic development can have many goals and be achieved in many ways, hence a generous approach is preferable with a shared view regarding what actually are desired outcomes.

References

Barnett, R. (2007). “Assessment in Higher Education: An Impossible Mission?” In Rethinking Assessment in Higher Education: Learning for the Longer Term, edited by D. Boud and N. Falchikov, pp. 29-40. London: Routledge.

Biggs. J. (2003). Teaching for Quality Learning at University – What the Student Does. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Biggs, J. (2010). Aligning teaching for constructing learning. The higher education academy. Available at: http://www.bangor.ac.uk/adu/the_scheme/documents/Biggs.pdf. [2013-02-05].

Boud, D. and Associates. (2010). Assessment 2020: Seven propositions for assessment reform in higher education. Australian Learning and Teaching Council. Available at: https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/Assessment-2020_propositions_final.pdf. [2015-09-23].

Boud, D. & Falchikov, N. (2007). Rethinking Assessment in Higher Education: Learning for the Longer Term. London: Routledge.

Bryman, A. (2011). Social Research Methods. Malmö: Liber AB.

Dahlgren, L-O., Fejes, A., Abrandt-Dahlgren, M. and Trowald, N. (2009). Grading systems, features of assessment and students approaches to learning. Teaching in Higher Education. Vol. 14:2, pp. 185-194.

Gibbs, G. (1999). Using assessment strategically to change the way students learn. I Brown, S. & Glasner, A. (red.). Assessment matters in higher education: Choosing and Using Diverse Approaches. Buchinghamshire: SRHE and Open University Press.

Gibbs, G., Hakim, Y., Jessop, T. (2014). The whole is greater than the sum of its parts: a large-scale study of students’ learning in response to different programme assessment patterns. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. Vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 73–88.

Gillett, A & Hammond, A. (2009). Mapping the maze of assessment: An investigation into practice. Active Learning in Higher Education. Vol. 10:2, pp. 120-137.

Harland, T., McLean, A., Wass, R., Miller, E. & Nui Sim, K. (2015). An assessment arms race and its fallout: high-stakes grading and the case for slow scholarship. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. Vol. 40:4, pp. 528-541.

Lindström, Å. (2016). A, B, C – U eller G? Vi får väl se!: Om bedömning och examination inom högre utbildning. Available at: http://lnu.diva-portal.org/

Linnaeus University. (2015). Linnéuniversitetets organisation. Available at: http://lnu.se/om-lnu/organisation. [2015-09-03].

Lundahl, C. (2006). Viljan att veta vad andra vet: kunskapsbedömning i tidigmodern, modern och senmodern skola. Diss., Uppsala universitet.

Marton, F. (2005). Inlärning och omvärldsuppfattning: en bok om den studerande människan. Stockholm: Norstedts akademiska förlag.

O’Donovan, B., Price, M. & Rust, C. (2004). Know what I mean? Enhancing student understanding of assessment standards and criteria. Teaching in Higher Education. Vol. 9:3, pp. 325-335.

Reimann, N & Wilson, A. (2012). Academic development in ‘assessment for learning’: the value of a concept and communities of assessment practice. International Journal for Academic Development. Vol. 17:1, pp. 71-83.

Rowntree, D. (1987). Assessing Students: How Shall We Know Them? London: Penguin.

Rust, C., Price, M. & O’Donovan, B. (2003). Improving students’ learning by developing their understanding of assessment criteria and processes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. Vol. 28:2, pp. 147–164.

Sadler, R.D. (2005). Interpretations of criteria‐based assessment and grading in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. Vol. 30:2, pp. 175-194.

Sambell, K., McDowell, L. & Montgomery, C. (2013). Assessment for learning in higher education. London: Routledge.

Snyder, B.R. (1971). The Hidden Curriculum. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG). (2015). Brussels, Belgium. Available at: http://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ESG_2015.pdf. [2017-01-23].

Taras, M. (2008). Summative and formative assessment: Perceptions and realities. Active Learning in Higher Education. Vol. 9:2, pp. 172-192.